I recently read a very well written and thought-provoking book, Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them, by Joshua Greene, which came out in 2013. I had so many thoughts that I decided to put them here rather than my usual short book review on StoryGraph. If you’re interested in one psychologist’s unexpected and unusual ideas about moral philosophy and moral psychology, please read on!

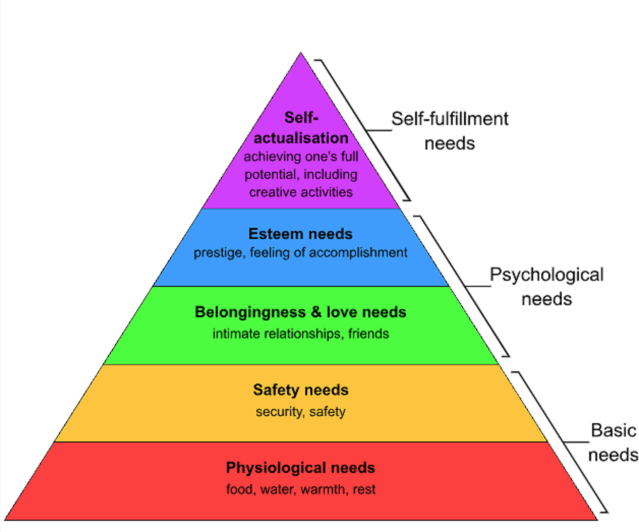

This very interesting book starts with the premise that our feelings tell us what’s right or wrong when it comes to interacting with people generally like ourselves. We feel concern for others who are physically near us, or sufficiently like us; we feel horror, revulsion, etc., at the idea of acts we consider immoral. However, people from different cultural backgrounds – those from different “tribes” – can have different takes on these situations. This is especially true for things one group considers sacred or blasphemous but others do not, but the problem can come up in conflicts about how to treat people, too. Greene tells us, thus, that our emotions help us for “Me vs. Others” problems but not so much for “Us vs. Them” problems.

Since part of my background deals with serious “Us vs. Them” problems, like genocide, I was very interested to learn what Greene would propose for how we should extend our morality from how we treat people our in-groups to include people from various out-groups.

Philosophy doesn’t give us many answers. We know in theory that we should treat all humans as equally human, or that we should value all living beings, etc., However, the practical side of understanding that out-group members are just as human as we are tends to be undermined when they seem strange or “backward” compared to people like ourselves. One answer is learning to extend our empathy to out-group members, by reading or watching stories about them that show us that they’re just like us in every way that counts, and that their differences are potentially cool rather than simply odd or maybe even wrong. Another answer is to think in terms of “rights” that belong to humans and to some extent to animals, and I’ll come back to the idea of rights below.

Religion doesn’t offer many answers either. The parable of the Good Samaritan fails when people don’t remember that Samaritans were a despised out-group – Jesus was teaching his followers that even someone you think is somehow a lesser person can be kinder than people who are just like you. Mr. Rogers, a universally beloved ordained minister, also taught inclusivity. On the other hand, just last night I was reading in the teachings of Confucius that you should “refuse the friendship of all who are not like you” (Analects IX.24, the Waley translation). I’m not qualified to understand the context of that teaching, but its meaning seems pretty straightforward.

Another way to understand “Us vs. Them” is at the level of groups. How should one group treat other groups? In the 20th century we developed the idea of genocide as a moral wrong – we should not destroy other groups. The idea of genocide has been extended to “cultural genocide,” which refers to the idea of eliminating a group without physical violence, necessarily, by encouraging its members to stop identifying with it. An example is the slogan of the Carlisle Boarding School, which worked hard to strip away the “Indianness” of the Native children who lived there: “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” However, there can be times when most people agree that a group ought to be disbanded – an obvious example is the Nazi Party in post-war Germany. Has philosophy addressed the idea of when that’s good and when that’s bad?

So I was quite interested to learn what Greene would have to say about these two “Us vs. Them” issues. Unfortunately (for me), it turned out his project was something altogether different. He wants to establish a “metamorality” that would apply when members of two “tribes” are part of the same system. For example, how do we decide what the laws should be for abortion if we have “pro-choice” and “pro-life” people offering competing arguments? He’s talking about Us and Them competing with each other for power and control over their common larger group – or else he’s talking about establishing moral rules to govern all humans.

Greene’s answer is a “practical” version of utilitarianism, which he calls deep pragmatism. Our collective goal, he says, should be to maximize happiness (or quality of experience) impartially. He emphasizes that the efforts to get there should be practical, rather than ideal – for example, we can ignore the idea that in theory, some person could be potentially capable of much more happiness than the average person, so that their preferences would tend to dominate. I assume that he would also dismiss the “Omelas hole” idea that Ursula Le Guin came up with in her story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” It’s about a city where everyone was perfectly happy and everything always ran smoothly, at the cost of one small child held in miserable captivity in a hole beneath the city. Every citizen eventually learns that their happiness comes with this cost. What would you do in that situation? Although Le Guin presumably meant it as a metaphor for systemic injustice, if taken literally it’s just a thought experiment that’s unlikely to happen in the real world.

So how do we get to “deep pragmatism”? I found Greene’s approach quite interesting.

Back in early 2022, when we were all addicted to Wordle, I wrote a blog post about our two basic approaches to thinking and problem-solving: Wordle, fast and slow. Whenever we take in new information, we experience an automatic response – it’s cool, it’s threatening, it’s exciting, it’s boring. Our emotional response involves emotion and our physical readiness to react (maybe fight-or-flight if it’s scary, maybe “let’s check it out!” if it’s intriguing). This quick and effortless response comes from “System 1 thinking.”

Sometimes, though, we can tell that the situation calls for more careful, conscious, deliberate thinking, which we call “System 2 thinking.” Usually, this System 2 thinking supports whatever emotional assessment we’ve already made! That’s known as motivated reasoning. But if we believe it’s important to have a more purely analytical, rational, unbiased response, we can make an effort to carefully set aside our emotional reaction (to some extent) and consider what the best response would be without it.

Greene’s insight is that we also use System 1 and System 2 for our moral responses to situations. He never refers to them as “System 1” and “System 2” (and he doesn’t even much discuss how these two systems are used elsewhere in processing information and making decisions), but he does provide the nifty analogy of using a camera – we can either use the “automatic mode” if we want to get our picture quickly, or “manual mode” if we think the photographic situation calls for more deliberate care with our settings.

For moral questions, then, he suggests that whenever there’s any sort of controversy about what is right, we should use our “manual mode” – our rational processes with our emotions set to the side – to discover which outcome is best overall. And he believes the best overall outcome is one that provides the most net happiness overall.

Greene develops his ideas by looking at how people answer the infamous “trolley problem.” The idea is that people are presented with an either-or question about the decision they would make. Personally, I have issues with whether this sort of decision fits with our plan to be practical and realistic, but let’s set that aside to see where Greene gets us. A trolley is coming down the track, and five people are standing on the track. Would you push someone onto the track, thereby stopping the trolley from killing the five people, but sacrificing that one person you had pushed? Most people say no, they wouldn’t push the person. But would you flip a switch, diverting the trolley onto a different track where one person is standing, so now the trolley will kill that one person instead of the five? Most people say yes. Greene says that both decisions are “rational” in that it’s better for one person to die than five, but our automatic emotional response is much stronger against killing one person by pushing them than flipping a switch to target them.

Greene and others have then used a bunch of variants on the question, redesigning the track in several rather odd ways, and discovered that two other features influence whether we’d make the “rational-but-too-emotionally fraught” choice of methods for killing that one person to save the other five. One is that we don’t want to use killing as a means, but we’re relatively okay with killing as a side effect (collateral damage). The other, related to that, is that harmful actions bother us more than harmful omissions (failures to act) do. All three together are bound up in the “pushing” scenario, so it feels most emotionally wrong to us. (As it should!) So he wonders what it would take for us to be able to make the choice that most bothers our conscience, which would lead to the greater good, and says it would be to step back and weigh evidence.

Greene makes a point of contrasting his approach to morality with the usual approach: recognizing and respecting human rights. I found this discussion quite interesting also. Usually, he says, we talk about “rights” when we want to present our subjective feelings as matters of objective facts – jumping ahead to being rational without taking the necessary step of detaching our emotions first. “Rights” allow us to rationalize our gut feelings without doing any additional work. On the other hand, once we’ve done that additional work of thinking about what’s objectively best overall, then he thinks it’s fine to talk about “rights” because, as he says, “the language of rights actually expresses our firmest moral commitments.” If there’s any controversy, though, that’s our signal (he says) to switching back into a more analytical mode and hashing it all out objectively. (Oooh, “switching”… did I just use a trolley pun?)

Incidentally, I was just looking at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations in 1948 and thus represents what most of the world considers to be best practices. Did you know that we all have a right to medical care, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, or disability? *ahem*

I liked seeing that Greene basically agreed with the point I was making in my all-time most popular blog post, on what’s wrong with Moral Foundations Theory. Jonathan Haidt says that liberals have two main moral foundations (harm/care and fairness) while conservatives have more foundations (loyalty, respect for authority, and purity/sanctity), with the implication that conservatives are thereby more “moral” than liberals. But Haidt ignores that the way they’re asking the questions isn’t about loyalty, authority, and purity generically – they’re asking the questions in the context of being part of a “tribe.” Conservatives are simply agreeing that they’re more tribal than liberals. Greene agrees with me about that. In my post, I also show that those on the political left are also known to make use of these same tools. For example, environmentalists care about different types of purity than tribal conservatives do – they’re more concerned about the quality of our air, water, soil, ecosystem health, etc., rather than sex acts, and they use a different source of authority, which they also respect – the life sciences, not religion. But they’re still enlisting those same foundations.

Moral Tribes was very interesting to read. However, I felt that the author’s project failed on its own terms. He kept stressing that his form of utilitarianism had to be realistic and practical, not idealized and theoretical. Yet he never acknowledged that the policy-makers he expected to step aside and think rationally about these morally laden issues would need to report their results to constituents who would, by and large, use System 1 to evaluate them – and very likely reject them for not saying things that match their intuition. And the idea that every human being would themselves submit to this “set aside our biases and weigh the evidence impartially” step is extremely unrealistic as well. It’s not unreasonable to conclude that something that fills us with deep distress is wrong.

(I also have to say that personally, I feel it would be horrific to flip that switch and kill the one guy on the second track. I’m not sure that I could do it. I don’t want to play God. So for me, it’s hard to base an entire system of thought on assuming that I would do so and getting me to agree that it’s equally “rational” to push that other guy onto the track. Sorry. I don’t even like imagining it. Would I be going too far if I were to say that subjecting the participants in psychological experiments to the trolley problem is itself maybe just a little bit morally wrong as well?)

Trolley photo source (cropped): Wikipedia, photographer Steve Morgan