Here in the United States, we are constantly seeing bad news.

At this point in my little essay, conventional writing practices call for me to list the problems I think we’re facing. That would let me signal to you, the reader, as to whether we’re in the same political camp and therefore whether it’s worth your time to keep reading. I’m not going to do that, for reasons that should become obvious – meanwhile, please trust me.

Whatever our politics, we’re all seeing that things are rough, for many of us. And we each have so little we can do, as individuals, to make things better. The list is short. We can vote for candidates who match our values and priorities. We can tell our elected representatives what we think. We can protest when things are going differently than we think they should. And above all, we can stay informed and build community, so that if the time comes that we need to be personally involved, we’ll know what to do.

I fully support our committed engagement to democracy and due process. And because I want us to stay engaged, I’m writing today to share a problem that’s become widespread – when our work to stay informed and build community can backfire on us.

One of our current favorite places to learn what’s going on and share it with others is in our social media feeds. We see lots of messages conveying the implications of various facts and findings. The people crafting these messages – memes and banners – are likely thinking that the more dramatic they are, the better – the more likely they’ll catch our attention and convince us it’s important to Do Something Now.

Here’s an example. The more we can reduce our emission levels for atmospheric greenhouse gases like CO2, the less climate change the Earth will experience in coming decades. Ideally, our target level should be zero, but that’s not realistic. We’re not going to all immediately stop driving gasoline-powered cars, heating our homes with fossil fuel products or electricity made from fossil fuel products, taking airplane trips, building with wood and concrete, etc. So the people who know much more than you or I do about what’s realistic and what the consequences might be have to pick a number, which is our target, and a date, by which we’d like to meet that target. Back in 2018, the number was 1.5°C for our overall warming, and the date was 2030. It’s a continuum, not an either/or thing. The closer we are to the target, the fewer the effects of climate change on our future selves and our families.

But numbers don’t catch people’s attentions like threats do, and a continuum is nowhere near as dramatic as either/or. If attention and drama is our goal, which it very well might be if we want people to act, we need to rephrase things. That’s why soon after that 2018 announcement, there were protesters waving banners telling us we had 12 years left to save the planet.

Twelve years! ACK!

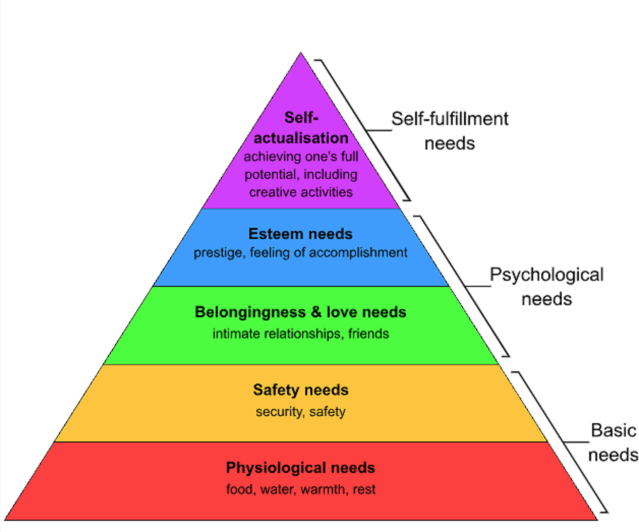

Whenever something is threatening our basic security – all those important things at the base of Maslow’s Pyramid like food, water, air, sleep, shelter, safety – our natural response is ACK, and we immediately focus all of our attention on getting those needs met.

When we’re learning about it from others, people with the best intentions who are trying to nudge us toward action, but the threat is not obviously immediately in our faces, we may still have the physiological reactions of ACK!, but we don’t have actions we can take that are guaranteed to put things right. And when we’re facing a continuous stream of messages like that, the effects of our continuous stream of ACK! responses will build up and can affect us profoundly.

This all assumes goodwill on the part of the people creating these banners and memes. When people believe what they’re saying but it’s wrong or misleading, that’s what we call misinformation. Sometimes, though, the messages we see are actually disinformation – the deliberate spreading of false or misleading information. For example, starting in 2016, a “troll farm” based in Russia used U.S. social media, especially Instagram, to discourage Black Americans from voting. And then, of course, people spread things along, and the effects can snowball.

So that’s social media. What about traditional media? For the most part, the news media are businesses. They need to minimize their expenses while maximizing their sales. To minimize their expenses, they usually can’t afford to spend much time on research – they have to go with whatever information is readily available, like government reports. To maximize their sales, they need flashy headlines – they need to find (or manufacture) the drama in the facts. They also need to focus on what’s happening right now – they can’t always invest in the slower stories. Today’s bad news is simply more dramatic than long-term good news. Hence, more ACK.

When we’re constantly exposed to ACK messaging, there are three logical directions we can go. First, there’s denial. We can protect ourselves by rolling our eyes and dismissing it all as nonsense, the ravings of hysterics. Seeing these messages loudly dismissed as ravings does little to build bridges with the people who aren’t sure where they stand.

Second, although we might think what we’re seeing is true, we realize that subjecting ourselves to these messages with no realistic way that we as individuals can fix these problems is harmful to us. So we opt out. We reject the context of public affairs as something that’s too much of a hassle, too harmful for our mental health, and we focus on our own lives.

But if we’re opting out from the world of politics, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t affect us. Many young people today are trying very hard not to think about the state of the world, but still believe it’s too messed up or that the world may not even be there in the relatively near future. It can be very difficult to commit to a productive path in life if one doesn’t believe, at heart, that there’s a point to even trying.

The third choice is to accept that it’s our responsibility as citizens to stay engaged. If the messaging is always negative, then we just keep treading water and feeling anxious, and maybe also depressed. When we’re under stress, we’re more impulsive and make worse decisions than when we’re relaxed. But when we’re facing big problems, we need to be confident that we can be our best selves.

Also, when we’re under stress, we oversimplify. It’s much harder to embrace complexity when our mental resources are taxed by anxiety and threat.

In his many best-selling books, the psychologist Steven Pinker makes the case that – despite what many of us think – life for humans has been getting considerably better. Personally, I find him exasperating. He’s oversimplifying in the other direction, generally ignoring racial issues and serious ongoing environmental problems. But he does have a point. Neither of my sons had to worry about getting drafted and shipped overseas to die in jungle warfare. I can name many people who have lived for decades after receiving cancer treatment. Skies and rivers and lakes are often cleaner than they were when I was born.

And it’s good for us to remember these things and celebrate them.

So today I want to tell you about FixTheNews.com, which I learned about back in August. It’s by a small team in Australia who collect and share solid, verified, GOOD news. You can subscribe for free and get an email every week or so with really encouraging news from around the world. You can also contribute financially, supporting their work and getting even more good news.

Just in the past three weeks, here are some things we’ve learned about:

- Only seven years ago, only 16.7% of India’s rural population had tap water, but that’s now up to 81%.

- Vaccination rates in Africa have increased dramatically, protecting more people against malaria and other dangerous diseases.

- China’s CO2 emissions may have peaked, and more than 90% of new investment in China supports clean-energy industries.

- New research shows that combining solar panels with farming could boost crop output hugely.

- The United Nations is providing one million hot meals a day to refugees in Gaza.

- Amazon watershed deforestation has reached an 11-year low.

We can’t replace our current news diet with “all good news,” but we can balance it with services like FixTheNews.com – which can improve our mental health and expand our capacity for news overall. Here are some potential side effects I can envision from having this kind of news in our lives:

- Reminders that the world really is a complex place after all, and many of our fellow humans are doing wonderful things

- Some glimpses of the bigger picture, so we can remember that political seasons change

- Inspiration for young (and older) people looking for ways to make a difference

- Simple moments of joy

So if you’re feeling overwhelmed with ACK, consider signing up for this service, or finding some other sources of positivity. We’re in it for the long haul, after all.