How did we get to be “civilized”? Here’s the big-picture story most of us have learned.

For hundreds of thousands of years, humans lived in small bands that wandered the land, hunting for meat and fish, and foraging for nuts, fruits, edible leaves and tubers, fungi, shellfish, and so on. Eventually some folks domesticated the various species of grazing animals, which gave them milk and sometimes meat, ready to hand.

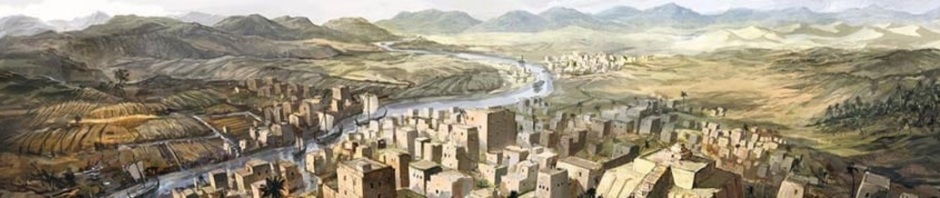

Then, about 10,000 years ago, grain crops were domesticated in a major agricultural revolution, and because grains can be stored, the surplus crops led to the rise of cities, in which hierarchies organized those crop surpluses, with a king at the top and a warrior class to defend the cities against outsiders. Similar stories are told for each of the great centers of early civilization: the Fertile Crescent in Mesopotamia, the Nile valley in Egypt, the Indus people of India, the earliest Chinese, and the great city-builders in Mexico and the Andes.

Eventually, the story goes, the intellectuals of Western Europe took things a step further and created modern democracy, inspired by the ancient Greeks. This step allowed us to transform our social lives into a much more fair system that echoed the egalitarianism of the early foragers.

Obviously, this is a self-congratulatory meta-narrative of Progress, although many have some ambivalence about it. For example, the ecologist Paul Shepard and other environmental writers have recast the story as a tale of loss and estrangement from the natural world.

However… I’ve just finished reading a fascinating book that explains how and why the story we tell about civilization ought to be much more complicated than the one I’ve just summarized. The Dawn of Everything, by anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow, purports to be, as its subtitle tells us, “A New History of Humanity.” They point out that the standard meta-narrative of civilization is misleadingly oversimplified and downright inaccurate.

Graeber and Wengrow explain that this story began with a French economist, A.R.J. Turgot, who believed that technological progress and a shifting in the relationship between humanity and the natural world was the basis of social improvement. Jean-Jacques Rousseau developed the story further and made it much more famous, but the whole idea of focusing on different types of sustenance as going through evolutionary stages was both new and specifically intended to respond to the harsh (and reasonable) critiques of European society that had been leveled by indigenous Americans. In other words, it was intended to put the Natives in their place – they didn’t have the same kind of technology Europeans had so they were more “primitive” and their ideas didn’t matter.

As Graaber and Wengrow explain, more recent archaeological findings have shown that the story is wrong, in a great many ways.

- It’s incorrect to assign people to one level of development based on how they live – some people lived in cities during one season and out foraging on the land at other seasons.

- It’s incorrect to insist that foragers didn’t settle and didn’t have hierarchies – a fact well known to those of us living in the Pacific Northwest, as many indigenous groups, especially the First Nations in British Columbia, were very wealthy, with hierarchical societies and no agriculture at all except for medicinal plants and plants producing luxury foods for feasts.

- It’s incorrect to tell us that agricultural revolutions rapidly transformed how people live, when in many places around the world it took about 3,000 years from the first evidence for farming and gardening to full-scale agriculture. People seemed to prefer the flexibility of getting their food from multiple sources. Just like today, in fact, a person might go elsewhere to find the bulk of their meal (hunting or fishing for them, shopping at a supermarket for us) and then come home and harvest some berries from their backyard to go with their dinner.

- It’s incorrect to tell us that prehistoric cities necessarily had major hierarchies – some of the most interesting recent archaeological digs have found cities where everyone’s home was approximately the same size.

- It’s incorrect to characterize the transition from foraging to agriculture as a type of progress, as we now know that many places that cultivated grains deliberately chose to give it up – it can be a trap to put all your eggs in one basket, waiting for months to get your harvest when you might have a drought or invasion to ruin it all.

- Above all, it’s incorrect to tell us that only European intellectuals could have rational debates about social choices and values. They focus especially on Kandiaronk, a politician and intellectual of the Wendat people (who we know as the Huron, living near the Great Lakes) whose critiques of European customs and religion were extensively circulated among Enlightenment thinkers. It’s thanks to him and other indigenous critics that the ideas of personal freedom and equality gained currency in Europe – up to that point, such ideas had been alien and suspect.

Yes, the Europeans did have technological advantages over much of the world, having eventually caught up with and surpassed the Chinese and the Muslims, but they weren’t as good at meeting basic human needs as the Wendat were. For many Native people, the idea that someone could be allowed to go hungry was shocking. Time and again, Europeans and European-Americans who had lived for a period among the Natives but then returned to their own people later changed their minds and went back to live with the Natives again. In general, the indigenous values and lifestyles led to greater happiness.

If so many elements of this social progress story have been shown to be wrong, why hasn’t the story been corrected? I got the impression that Graeber and Wengrow were blaming the way academia works these days. Researchers get ahead by specializing, and if you discover that something about the story isn’t true for the group you’re studying, you assume that it’s an exception to a general rule. It’s not often that anyone takes the time to conduct a wide-ranging synthesis, as Graeber and Wengrow have done.

And the story is flattering to who we are today, so what’s the motivation for saying it’s wrong?

Ironically, for a book attacking the oversimplification of our collective history, the places where the book falls short is when it oversimplifies.

The one instance that actually irked me was the chapter in which they tell the story of the Kwakiutl people of British Columbia and the Yurok of northern California as societies choosing to define themselves in part against each other, being “neighboring populations” (p.180). They tell us that the Kwakiutl, who valued boastfulness and extravagance, based their economy on fishing, and the Yurok, who valued personal modesty, based theirs on fishing and acorns. Their argument seems iffy to me in several ways (I’m not convinced that adding acorns matters all that much), but one key issue is that more than 600 miles and dozens of other communities separate the two societies.

(It reminded me of a woman I knew years ago, who had moved from Boston to San Francisco. One day she suggested to her husband that they drive up to Seattle for the afternoon – the two cities had seemed like neighbors to her, yet it’s a 14-hour drive…)

Between the Kwakiutl and Yurok lands there was quite a considerable space – a space that today comprises the entire states of Oregon and Washington. As someone who grew up and still lives on that land, I’m skeptical of the premise that traditional people necessarily cared so much about defining themselves in terms of differences between themselves and other groups. The people on our coast, including the Siuslaw on whose land I was born, had salmon-based economies like the Kwakiutl, while the Kalapuya people, whose territory now includes my home in Eugene, and who basically lived right next door to the Siuslaw, had an acorn- and camas-based economy. I’d be surprised to learn that they spent a lot of energy on making sure their cultural practices were different from each other, even though (unlike the Kwakiutl and Yurok) they really were neighbors.

Other topics in the book seemed oversimplified because of space constraints, which is saying something when the book was almost 700 pages long. I would like to have learned more about the evidence they’ve found for three social bases of power (control of violence, control of information, and individual charisma). Graeber and Wengrow had planned more books, in which they might have gone into these issues in greater depth. Unfortunately, David Graeber died three weeks after they’d completed the manuscript, evidently from long-term complications of Covid.

Their overall message was solid and well-supported, however. Groups of humans have experimented many, many times with how they choose to organize themselves. There has never been a one-size-fits-all answer, only answers that did well or poorly at meeting the needs of the groups and their members for a given era. We are not destined – or doomed – to live as we do now forever (or to die out when our current practices fail). As our circumstances change, we can choose to be more flexible. We can evaluate different practices, and different stories, and decide what works best for us.

Image source: https://www.ancient-origins.net/sites/default/files/field/image/mesopotamia-painting.jpg