Let’s imagine you’ve been invited to speak to your entire country! You have to talk about current events (sorry, no sharing your hobbies or bragging about your kids), and the purpose of your talk is not just to educate, but to inspire the public. You want them to act.

As you plan your speech, there are two decisions you’ll need to make. First, pick a topic – any topic will do. It’s your second decision that I’m interested in, and it is: How do you want to make your listeners feel?

Every time we talk about the groups we’re in, like our country, our ethnic group, or even our species, we’re often making the case that things are getting better or worse. We may be worried about what immigrants, or climate change, or income inequality will do to our country. We may be setting some worthy goals that we should all work together to meet, like eliminating world hunger or sending astronauts to Mars. We may just want the world to know that our people are here to stay.

The special kinds of stories we’re telling are called “meta-narratives.” Leaders can use these stories to influence us to feel these emotions, and emotions lead to action. If we recognize what they’re doing, we can make up our own minds and be less susceptible to others’ persuasion.

When you’re planning your big speech, depending on the emotions you’re trying for, you’ll probably choose one of these twelve “super-stories,” the emotional genres for meta-narratives:

Stability. Things are always the same. You can rely on it, you can feel confident. Conversely, if you want something new and different, this story can make you feel stifled or demoralized. Things are always the same.

Rome, the Eternal City:

Recurring Saga. Things regularly get better, then worse, then better again, on and on, like a pendulum swinging back and forth, from “good” to “bad.” If you have a two-party system of government, that’s a familiar experience.

Usually, when you have an election, the party that’s out of office promises a Course Correction, which is just a piece of the same Recurring Saga. We feel a sense of security because it’s so predictable, and optimism, because things can always get “fixed” in our own direction again. Or, of course, frustration, if it seems we never get anywhere.

Recurring Crises. A repeating pattern can also be more dramatic. Anthropologist James Wertsch says this is how Russians experience their history: a long series of invasions that they have to repel, again and again. Things may never be good – they just regularly start and stop being bad. This storyline leads its people to feel anxiety, fear, and disorientation, punctuated by moments of relief and self-congratulation.

Progress. America’s story is very different. Our story is about Progress – more prosperity, more opportunities, always building and growing, solving problems like cancer and overcoming limitations like our finite supply of fossil fuels. Both the Left and the Right want progress, but they have different goals. The Republicans traditionally want their Progress to mean more prosperity and more safety and security. The Democrats traditionally want their version of progress to mean, yes, more prosperity, but also more fairness in how it’s distributed. Both visions of the future need their progress to be backed by Stability, because you need predictability to be able to make plans for the future, whether that’s building a business, getting an education, raising a family, or looking forward to retirement.

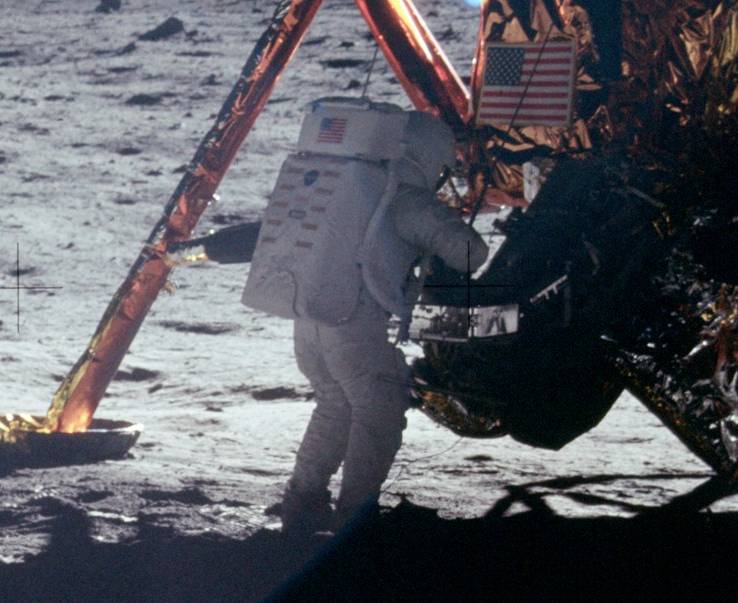

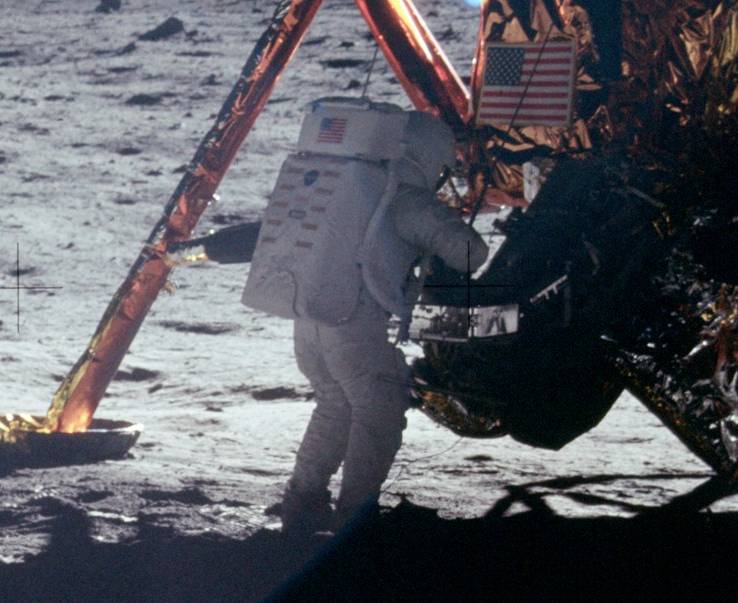

One variant of Progress is a Mission. Here the people set a goal and work hard to make it happen. This could be like Manifest Destiny, when the United States sought to conquer all the land across the continent, from sea to shining sea. It could be like Woodrow Wilson, telling us it’s our job to make the world safe for democracy. Or it could be to be the first country to put a human being on the moon. A Mission, and Progress more generally, lead their people to feel optimism and satisfaction.

Neil Armstrong arrives on the Moon:

Transformation. Another way to make changes is more abrupt. Here the idea is to sacrifice some of our stability to get somewhere in a hurry. With a Transformation, some people feel joy, while others feel disoriented with the loss of Stability. Some classic examples would be the French Revolution, or Chairman Mao’s Great Leap Forward. Bernie Sanders uses “revolution” language too, although he’s not advocating such an extreme transformation – he wants us to use our existing laws and processes to get America caught up with the rest of the world.

Miracle. The final type of improvement story is when a group reappears and begins to flourish after a disaster – it’s a tragedy with a happy ending. Some Native American writers describe their people’s story that way, like in a film I saw a few years ago, United by Water, where several Pacific Northwest tribes felt their nations had essentially died, until they worked together to reassert themselves. Many Jews felt like this about the forming of the modern nation of Israel. The feelings for a Miracle (or as J.R.R. Tolkien called it, a “eucatastrophe”) are joy and relief.

Prior Fall. We have negative storylines as well. One of the most familiar is the Prior Fall. In this storyline, things were very good for a group of people, but that was lost. We have Adam and Eve, exiled from Eden.

Expelled from Eden:

(c) Walker Art Gallery; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Or we have prehistoric humans, living in harmony with nature, or pre-industrial humans, who had their own harmony with nature. This is an airbrushed look back into the past. It’s not that things were actually better for those early humans, but looking back from the present, those earlier times can feel better – more peaceful, less harmful to the environment.

Specific groups sometimes look back into their past and think things were much better for them then, too. Sometimes they were; at other times, again, they’ve idealized that past. When we compare an ideal past to the present, we may feel shame about the lesser status of our current group. We may feel guilt, if the fall was our fault, and we may feel anger if we think some other group was to blame.

Tragedy. A tragedy is a loss that’s much more fresh. It’s recently happened, and it feels like it’s still ongoing and that nothing can be done. The same shame or guilt or anger still apply, but also frustration. Good examples include when one group takes land away from another, as the U.S. did to its native people, and as the founding of modern Israel did to the people who were already living in Palestine. If a group romanticizes what used to be and what might have been, they can invent their own Tragedy storyline

Some think the Civil War outcome was a Tragedy:

Looming Catastrophe. And of course, there’s the negative storyline where the loss is in our future. Climate change is making our weather more extreme, with more hurricanes and wildfires (in fact, one has kept the people of my city indoors for a week now), and in the future it could be much worse. Alternatively, we might be concerned about unchecked immigration or other changes to our communities that could change our way of life. For those attuned to the Looming Catastrophe storyline, the emotions they feel include anxiety, fear, and urgency.

Those are the simple storylines. If we combine them we can get three more genres that are just slightly more complex, but they’re especially powerful.

Crossroads. A Looming Catastrophe implies a crossroads – either we figure out how to stay on our usual course, or everything goes south. But any major decision point is a Crossroads, like if we’re deciding whether to make a significant policy change, or have a revolution, or go to war. One branch takes us on one storyline, and the other takes us elsewhere. Emotions at a Crossroads include anticipation, anxiety, and whatever else may be associated with each of the two paths, as well as a sense that the time we live in is important and meaningful.

Restoration. If we combine a Prior Fall that takes us from an idealized past to a degraded present, with a Transformation that lifts us back to that ideal state again, then we have a Restoration. This storyline may be extra-powerful because it fits the conventional story prototype, in which things are okay, but then some problem arises, which has to be fixed to yield a resolution.

The Restoration storyline is the basis for Christianity – humanity lived in Eden, but they fell from grace, and now we live in a sinful world, but believers can hope to go to heaven. It’s also the basis for nationalism – a people have a wonderful mythic past, but they were conquered or dominated by others, and they want their sovereignty restored so they can achieve their rightful place in the world.

The Restoration storyline combines all the emotions of its underlying components, and it often also comes with an extra sense of drama, even melodrama, especially if you add in a Crossroads and danger, like conflict with another group or some other pending disaster.

Triumph. Finally, we have the storyline that comes from combining achievement, as in Progress or Transformation or Restoration, with permanent Stability thereafter, resulting in feelings of pride, security, and confidence. This storyline also uses basic narrative psychology, with a period of suspense that is resolved, just like when you read a book or watch a movie and at the end expect closure, our happily ever after. Or, as some might say, our “Final Solution” – the Holocaust was intended to fit this genre.

Once we’ve achieved a Triumph, we’re extra-motivated to keep its stability. A modern example comes from our own recent history – after the Cold War, the United States was quite satisfied to find itself the “lone superpower.” Its expectation that it now had everything under control was thoroughly dispelled by the 9/11 terrorist attacks, which were extra shocking because the U.S. thought it had already reached closure on its role in the world.

So there we have it, twelve “super-stories” and a few variants – emotional genres for meta-narratives. This list is certainly not exhaustive; it just illustrates many we’re familiar with today. At other times and places, people might understand their group’s history very differently. For example, time doesn’t even necessarily move forward! Mircea Eliade, a famous scholar of religions, describes societies where religious practices allow people to experience mythic times from the distant past, an Eternal Return. With a meta-narrative like that, the world is experienced as endless cycles – very much like in Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time fantasy series. Others sometimes describe our progress, catastrophes, and so on as stages in much larger eras, beyond the scope of human lifetimes, but if we think in those terms we may tend to feel dwarfed by inevitabilities beyond our control. We might just give up.

The next time you hear a leader telling you about their vision for the future, see if you can recognize one or more of these stories. And then decide for yourself. Does it fit the facts? And is it fair, not just to the group telling the story, but to the other groups appearing in the story? If not, how would you tell the story differently? If you had the chance, what would you say to your fellow citizens?

* * *

I’m writing a book on this topic, and I could use your help. An important part of the publishing process these days is for the author to be able to show the publishers that people are interested in their work. If you enjoyed this post, please “like” it and share it on social media. If you’d like to read future posts, please “Follow” by entering your e-mail address at the top of the right-hand column. Both of those steps will help me show the publishing world that people are listening. Thank you!

Is it the awe-inspiring Spartans? For some of 300’s fans, especially, this could be true. Its cinematic style certainly glorified the Spartan world – where, ironically, freedom was not valued. Ancient Sparta could serve as a prototype for militaristic fascism. Newborns not meeting government standards were killed, and those who survived weren’t allowed to live with their parents, nor could young married couples live together. Plutarch tells us that once a year, some of the men who had inherited Spartan citizenship were allowed to freely murder any of the vast majority who had not. Adolf Hitler praised Sparta for its eugenics program and bloodline purity, and Spartan training methods inspired the curricula of elite Nazi schools. Sparta is shocking – but of course, that sells movie tickets.

Is it the awe-inspiring Spartans? For some of 300’s fans, especially, this could be true. Its cinematic style certainly glorified the Spartan world – where, ironically, freedom was not valued. Ancient Sparta could serve as a prototype for militaristic fascism. Newborns not meeting government standards were killed, and those who survived weren’t allowed to live with their parents, nor could young married couples live together. Plutarch tells us that once a year, some of the men who had inherited Spartan citizenship were allowed to freely murder any of the vast majority who had not. Adolf Hitler praised Sparta for its eugenics program and bloodline purity, and Spartan training methods inspired the curricula of elite Nazi schools. Sparta is shocking – but of course, that sells movie tickets. I would say that the main value of Thermopylae comes from the life of a man born about ten years later. Socrates, the philosopher later called a “gadfly” by his pupil Plato, taught people to question assumptions, think carefully about the implications of our beliefs, and seek Justice and a higher Good. Late in life, Socrates was arrested and imprisoned (freedom of speech not being a feature of Athenian democracy). He was charged with the crimes of teaching the young people of Athens to think critically about its beliefs and values, that is, “corrupting the minds of the youth” and “failure to acknowledge the gods of the state.” He refused an opportunity to escape and accepted his execution by drinking poison hemlock.

I would say that the main value of Thermopylae comes from the life of a man born about ten years later. Socrates, the philosopher later called a “gadfly” by his pupil Plato, taught people to question assumptions, think carefully about the implications of our beliefs, and seek Justice and a higher Good. Late in life, Socrates was arrested and imprisoned (freedom of speech not being a feature of Athenian democracy). He was charged with the crimes of teaching the young people of Athens to think critically about its beliefs and values, that is, “corrupting the minds of the youth” and “failure to acknowledge the gods of the state.” He refused an opportunity to escape and accepted his execution by drinking poison hemlock.

Nottingham, he’s a part of our cu

Nottingham, he’s a part of our cu

But imagine you’re thinking of putting all your retirement savings into a gorgeous tropical island property that’s barely a foot above sea level. Now you really need your beliefs to be accurate, and you’ll likely want to put some effort into knowing and verifying the facts behind the potential belief we’ve been offered – doing some actual thinking. You’ll listen to scientists, collect your own data, learn what you can about probabilities and risks, and try to overcome whatever natural biases we all have.

But imagine you’re thinking of putting all your retirement savings into a gorgeous tropical island property that’s barely a foot above sea level. Now you really need your beliefs to be accurate, and you’ll likely want to put some effort into knowing and verifying the facts behind the potential belief we’ve been offered – doing some actual thinking. You’ll listen to scientists, collect your own data, learn what you can about probabilities and risks, and try to overcome whatever natural biases we all have.